A tiny cattle tick is causing huge economic damage to farmers and ranchers around the world. A University of Nevada, Reno researcher who pioneered tick research to help reduce the incidence of Lyme disease in humans has been awarded a prestigious Fulbright U.S. Scholar Award to apply her research to try to unlock control of ticks effective method.

Monika Gulia-Nuss, associate professor and director of graduate programs in the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology in the university’s College of Agriculture, Biotechnology and Natural Resources, is working closely with researchers in Uruguay Cooperating, the Uruguayan government is committed to protecting its natural resources. Up to 90% of cattle infected with tick-borne fever will die, and tick damage to cattle hides affects the leather industry, and tick-borne diseases can reduce milk production.

Gulia-Nus has made important new advances in understanding the genetic code of ticks, starting with the deer tick, which carries the Lyme disease bacteria that infects humans. Over the past decade, her lab has developed innovative tools to analyze and modify the ability of deer ticks to transmit pathogens.

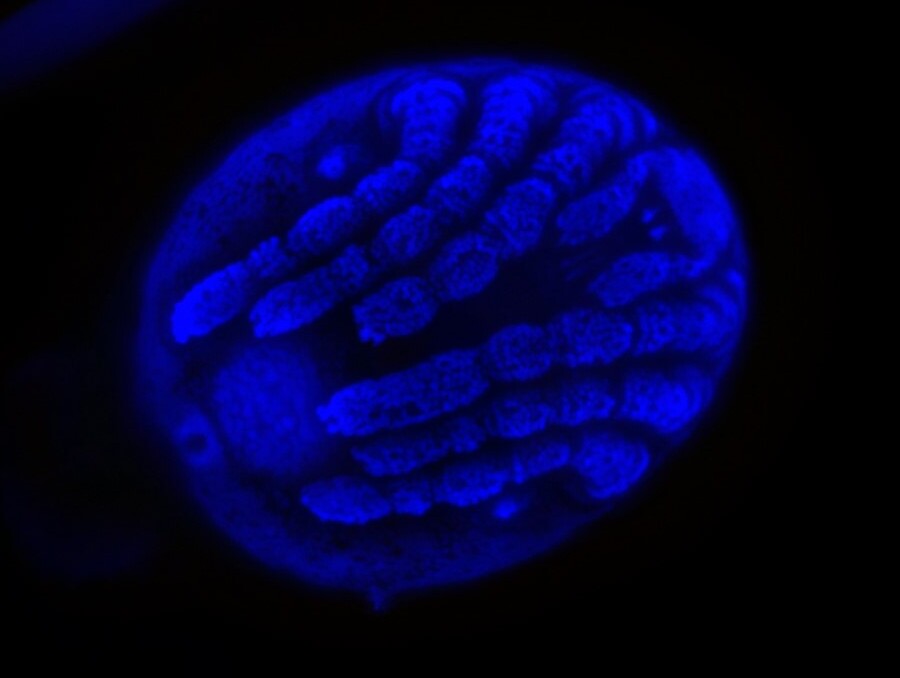

Generally, genetic modification relies on injecting genetic material and fluorescent markers into tiny embryos — whether ticks, mosquitoes or larger animals — so scientists can observe the activity of the target genes.

But researchers have run into obstacles in their attempts to inject tick eggs, which have a hard shell, high pressure inside and a tough wax coating that female ticks use to provide further protection.About two years ago, Gulia-Nuss and her researcher husband, Andrew Nuss, an associate professor in the university’s Department of Agriculture, Veterinary and Range Sciences, announced that they had successfully overcome these challenges, opening the door to injection of tick embryos and possible genetic modification.

“There is a huge need for the development of genetic tools for tick research,” Gila-Nous said. “Our deer tick methods have been adopted by many laboratories around the world, and we have trained many scientists in our laboratories to implement these methods.”

A more complex mystery

But Gulya-Nus acknowledges that cattle ticks are more challenging than deer ticks. First, the cattle tick’s genome is large and complex—twice the size of the human genome—and the genome has not yet been fully mapped.

This is crucial as Gullia-Nous seeks to identify genes in cattle ticks that could be targeted for genetic control or modified insecticides. Additionally, a better understanding of tick genetics may help develop effective vaccines for tick-infested cattle.

Gulia-Nuss and Michael Pham, a research scientist in the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, will travel to INIA Colonia in southwestern Uruguay in June. There, Gulia-Nuss and Pham are also conducting research as part of the university’s experimental station, where they will collaborate with INIA researchers Alejo Menchaca and Pablo Fresia of the Pasteur Institute in Montevideo, Uruguay, to establish a tick-rearing facility. kit.

In early 2025, Gullia-Nus will return to Uruguay for a three-month tour of duty supported by a Fulbright U.S. Scholar Award. During this time, she will inject thousands of tick embryos to better understand their genetic workings. She also hopes to start some genetic modifications.

Given the size of the cattle tick genome and the gaps in existing knowledge, researchers will be prepared to overcome several challenges.

“However, we are up to the challenge, and our previous studies of two other tick genomes will help us address possible issues that may arise,” Gulya-Nus said.

global cooperation

The highly competitive Fulbright U.S. Scholar Award (only about 10% of applicants are approved each year) is designed to build collaboration between scholars from the United States and the rest of the world. The award supports the researcher’s travel, accommodation and other expenses; the research institution in the host country funds the research itself.

The Uruguayan government strongly supports cattle tick research. Even 25 years ago, economic losses caused by cattle ticks in Uruguay were estimated at nearly $33 million per year. Currently, the only way to control cattle ticks is through the heavy use of chemical pesticides. But ticks are becoming resistant to these chemicals, and residual chemical residues could limit ranchers’ ability to sell their animals.

Although this tick is only found in a small strip of the southern U.S.-Mexico border, it is found in nearly every tropical or subtropical region of the world where cattle are raised. Uruguay is one of the hardest-hit regions.

“Uruguay’s economy is highly dependent on agriculture, especially cattle breeding. Rinderpest ticks are a huge economic problem in the country, and the Uruguayan government is committed to research and development of genetic control methods for ticks,” Gulia-Nuss said.

That’s why it’s particularly noteworthy, she says, that Uruguayan scientists are looking for collaborators in as far away as Nevada.

“Uruguay only offers one Fulbright research award each year,” Guglia-Nus said. “Receiving this award at the University of Nevada, Reno emphasizes the quality of research at our university. Our team, which has been working on tick research, is honored and excited to collaborate with colleagues in Uruguay on this important project.”

#University #Nevada #Reno #researchers #work #combat #deadly #cattle #tick #University #Nevada #Reno

Image Source : www.unr.edu