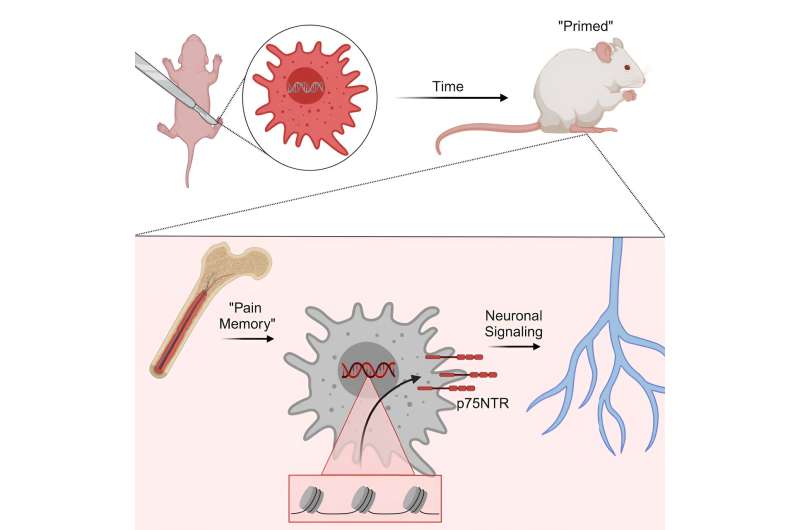

Injuries early in life can genetically alter the way the body’s pain response systems develop, leading to a pain “memory” that affects responses to injuries that occur years later, a study suggests. cell report Published by experts at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital.Image credit: Cell Reports and Cincinnati Children’s Hospital

In recent years, a growing body of research has shown that the body can “remember” the pain of newborn injuries, including life-saving surgeries well into adolescence.

These early experiences appear to change the way children’s pain response systems develop at a genetic level, leading to more intense responses to pain later in life. This change also appears to be more common in women.

Now, research led by experts at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital has pinpointed how and where the genetic changes that create this lasting memory of pain occur.According to their research published online on April 18, 2024 in the journal cell reportkey changes occur in developing macrophages—one of the main elements of the immune system.

“Our experiments help further confirm how pain memory affects female newborns over longer periods of time. Specifically, our data show that epigenetic changes occur in macrophages after injury early in life (which occur after birth). changes and inherited genetic variants), which in turn promotes a greater pain response to other injuries that occur later in life,” said corresponding author Dr. Michael Jankowski, associate director of the Center for Pediatric Pain Research at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital.

Dr. Adam Dourson, currently at Washington University in St. Louis, is the study’s lead author.

Experiments showed that male mice that experienced similar early-life insults showed the same epigenetic changes but did not maintain the same long-term pain memory as females. Further tests also showed that changes in the p75NTR gene could be found in human macrophages.

In female mice, pain memory effects were detected for more than 100 days after the initial injury. The incision causes stem cells in the bone marrow to produce macrophages, which are “primed” to respond more strongly to the injury, thereby increasing pain.

For humans, a similar time frame is about 10-15 years.

“We were surprised that a single local insult so dramatically altered the systemic macrophage epigenetic/transcriptomic landscape,” said Jankowski.

This new understanding of neonatal pain memory highlights fundamental differences between the genetic activity of the still-developing neonatal immune system and the mature system of adults. This means determining how surgeons and care teams adapt rehabilitative care for newborns and baby girls will be complicated.

“Simply changing the dose of analgesics may not be the answer. There is always a balance between controlling pain and minimizing the harmful side effects that existing medications can have. Instead, our findings point to the need to develop more specific, targeted treatments.” The approach prevents macrophages from reprogramming in response to injury,” Jankowski said.

Next step

More research is needed to use this new information to develop therapies to control immune “pain memory.”

In this study, blocking the p75NTR receptor in young mice indeed impaired the ability of macrophages to communicate with sensory neurons and partially prevented prolonged pain-like behavior. However, it is unclear whether a similar approach can be safely used to target human macrophages.

“Emerging technologies appear to be able to specifically block the p75NTR receptor in macrophages, but much more research is needed before this approach is ready for human clinical trials,” Jankowski said.

In addition to Dourson and Jankowski, Cincinnati Children’s co-authors include Adewale Fadaka, Anna Warshak, Luis Queme and Megan Hofmann, of the Department of Anesthesiology; Aditi Paranjpe, Division of Bioinformatics; Benjamin Weinhaus and Daniel Lu Daniel Lucas, Division of Experimental Hematology and Cancer Biology; Heather Evans and George Deepe, Jr., Division of Infectious Diseases; and Omer Donmez, Carmy Forney, Matthew Weirauch and Leah Kottyan, Center for Autoimmune Genomics and Etiology.

More information:

Adam J. Dourson et al., Macrophage memory of early life injury drives neonatal nociceptive priming, cell report (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.celrep.2024.114129

Provided by Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center

citation: Immune cells carry lasting “memories” of early pain (2024, April 18), Retrieved April 20, 2024, from https://medicalxpress.com/news/2024-04-immune-cells-memory -early-life .html

This document is protected by copyright. No part may be reproduced without written permission except in the interests of fair dealing for private study or research purposes. Content is for reference only.

#Immune #cells #lasting #memory #early #pain

Image Source : medicalxpress.com