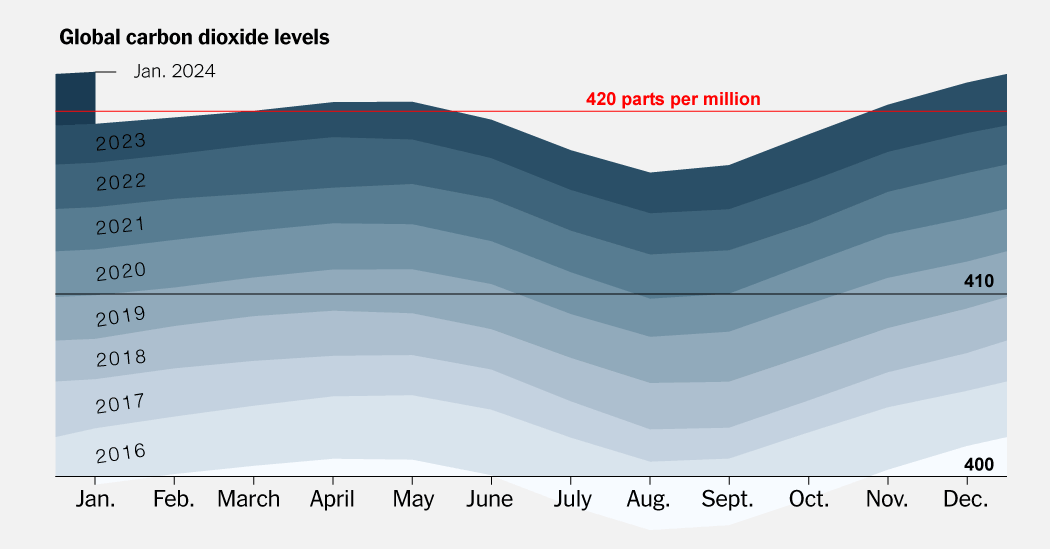

Source: NOAA Global Monitoring Laboratory

This chart shows the number of carbon dioxide molecules per million dry air molecules per month. Due to seasonal differences, levels in May are higher than in August.

Carbon dioxide acts like the Earth’s thermostat: the more carbon dioxide in the air, the warmer the planet becomes.

In 2023, global greenhouse gas concentrations rose to 419 parts per million, an increase of approximately 50% compared to before the industrial revolution. This means there are about 50% more carbon dioxide molecules in the air than there were in 1750.

As carbon dioxide accumulates in the atmosphere, it traps heat and warms the planet.

Carbon dioxide increases and temperatures rise

Source: NOAA (carbon dioxide); NASA (temperature)

This chart shows changes in global surface temperatures and changes in global carbon dioxide levels relative to 19511980. The dashed line shows the trend line.

Every extra bit of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere increases warming, which is why climate scientists stress the need to get to zero emissions.

Currently, carbon dioxide levels are rising at a rate close to record highs.

Last year saw the fourth-highest annual increase in global carbon dioxide levels, according to data released earlier this month by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Global Monitoring Laboratory.

Annual changes in carbon dioxide levels

Source: NOAA Global Monitoring Laboratory

This chart shows the annual increase in global carbon dioxide levels. In 2023, its growth rate will be approximately 2.8 per million.

Long-term increases in carbon dioxide levels are caused by the burning of fossil fuels and other human activities such as deforestation and concrete production.

But there are also a lot of changes from year to year, as you can see in the table above.

How much carbon dioxide levels rise in a given year depends on two factors: how much fossil fuels are burned globally, and how much of those emissions are absorbed by land and oceans.

Consider the first factor: While global clean energy production is indeed increasing, so is the demand for energy.

Fossil fuels bridge the gap. This is why global fossil fuel emissions remain at record highs (after briefly declining during the pandemic). According to Global Carbon Budget forecasts, this number will remain at a high level in 2023.

Not all of these emissions end up in the air. Oceans and land absorb about half of the carbon dioxide emitted by humans, leaving the rest in the air, said Glenn Peters, a senior fellow at the Cicero Center for International Climate Research.

Where do carbon dioxide emissions go?

Source: Global Carbon Budget

This chart shows the net emissions of carbon dioxide absorbed by the atmosphere, land and oceans. These emissions are produced by the burning of fossil fuels, deforestation and other human activities. Data excludes 2023.

This one-half figure is an approximation. It varies from year to year, depending on weather conditions and other environmental factors, causing the jagged lines you see in the image above. For example, during warm, dry years with frequent wildfires, the land may absorb less carbon dioxide than usual.

Doug McNeil, who studies these effects, said that as the planet warms further, climate scientists expect land and oceans to absorb a smaller proportion of carbon dioxide emissions, causing more carbon dioxide to end up in the air.

Lan Xin, chief scientist for NOAA’s global carbon dioxide measurements, calls natural absorption a carbon discount.

“We’re paying attention to it because we don’t know when the discount is going to go away,” she said.

In addition to carbon dioxide, levels of other potent greenhouse gases such as methane and nitrous oxide are rising, further exacerbating warming.

an extraordinary year

2023 will be unusually hot, both on land and sea. (The ocean absorbs more than 90 percent of the excess heat caused by global warming.) It was the hottest year on record in more than 170 years, exceeding even scientists’ predictions.

El Niño, a weather pattern that tends to increase global temperatures, was a factor in the extreme heat in 2023. During El Niño, warm ocean currents in the Pacific cause warmer and drier weather in the tropics. This can lead to drought, slow tree growth and increase the risk of wildfires.

When this happens, the land tends to absorb less carbon dioxide, and more carbon dioxide ends up in the air. Several climate scientists say that may be why carbon dioxide levels rose much more sharply last year than in previous years.

Return to zero

Current high emissions make the climate goal of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius increasingly difficult to achieve.

Experts say that to limit warming to this threshold, countries will need to put the brakes on global emissions and reduce them to near zero by 2020. about ten years. Some are even considering more extreme technological solutions to help close the gap.

Even if global emissions were reduced to half their current levels, we would continue to add carbon dioxide to the air, causing further warming.

To stop warming, you need to bring them essentially to zero, Mr. McNeil said.

The amount of warming depends on how long it takes for this to happen.

On the one hand, clean energy investment is booming and global renewable energy production is rising. But energy demand is also expected to rise, coal-fired power plants are still under construction and some sectors of the economy, such as construction and manufacturing, are harder to decarbonize, making the task ahead challenging.

Mr McNeil said even if global temperatures exceeded the 1.5 degree threshold, every fraction of a degree mattered.

The closer to this threshold, the better.

About data

NOAA’s annual global carbon dioxide measurements are an average of thousands of measurements taken near sea level at about 30 locations around the world. To account for local differences in humidity, dry air is used for measurements.

#Carbon #dioxide #levels #crossed #milestones

Image Source : www.nytimes.com