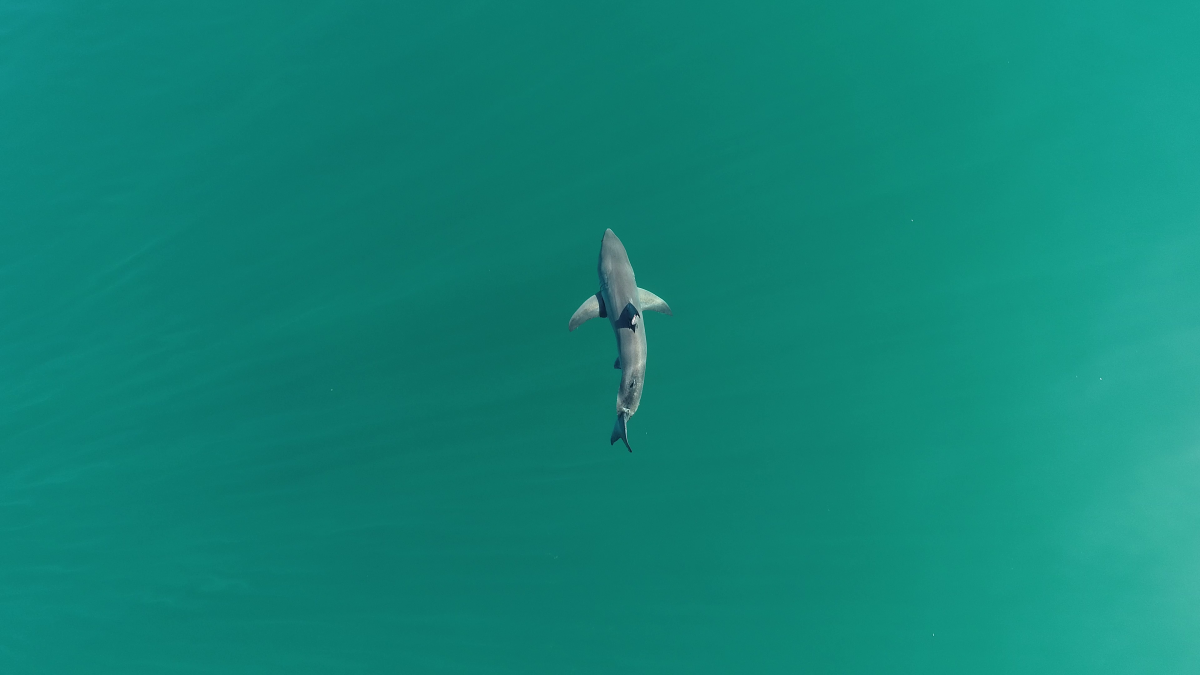

A new study finds that baby great white sharks like to lurk in shallow waters close to shore.

Marine scientists from California State University, Long Beach, have demonstrated this for the first time and solved one of the long-standing mysteries surrounding great white sharks.

It is difficult to document juvenile great white sharks and their breeding areas due to the elusiveness of the species. Scientists have known that baby white sharks spend their time in conservation areas when they are born, but their exact location remains a mystery and sightings are extremely rare.

New findings published in journal Frontiers of Marine Science, important not only for species research but also for conservation purposes. Scientists also believe they could help protect the public from “negative shark encounters” on beaches around California.

Although shark attacks on humans are very rare, they can happen when humans and sharks are in close proximity. During the warmer summer months, more people tend to come to the shallow water areas near beaches, which are the favorite places for baby sharks.

“This is one of the largest and most detailed studies of its kind. Because large numbers of juvenile fish share nearshore habitat around Padaro Beach, we can understand how environmental conditions affect their movements,” said senior author Dr. Christopher Lowe explain.

“You rarely see great white sharks displaying this type of protective behavior elsewhere.”

Patrick Rex

To make their findings, Lowe and colleagues tracked 22 young great white sharks between 2020 and 2021 using sensor transmitters.

The study was paused only during the winter when juveniles are out at sea, and researchers continue to study the depths and temperatures they prefer.

They found that young great white sharks dive to their deepest depths at certain times of the day: dawn and dusk. They also lurk closer to the surface in the afternoon, when daytime temperatures peak.

Overall, the findings suggest that juvenile great white sharks must constantly move based on preferred temperatures.

“We found that juvenile fish directly change their vertical position in the water column to maintain between 16 and 22 °C and, if possible, between 20 and 22 °C. This is probably their maximum temperature in the nursery The best choice for chemical growth efficiency,” first author Emily Spurgeon, a former master’s student and now a research technician on Lao’s team, said in the statement.

As a result, they found that juvenile great white sharks live mainly in shallow waters.

“Our results indicate that water temperature is a key factor in attracting adolescents to the study area. However, many locations along the California coast have similar environmental conditions, so temperature is not the whole story. Future experiments will look at individual relationships, e.g. to see Are certain people moving in tandem between daycares,” Spurgeon said.

Baby great white sharks are left to their own devices after birth. Their nurseries are often located in protected bays, where the pups can hide from predators until they are able to survive in the open ocean.

For an area to be classified as a great white shark breeding site, there must be evidence that juvenile white sharks occur there more frequently than elsewhere. They also have to stay there for a long time and reuse the same area for years.

Although great white sharks remain an elusive species and there is still much to learn, scientists are making progress.

Earlier this year, a live baby great white shark was discovered in the wild for the first time in California. Baby sharks had never been observed before. In fact, their mating rituals and childbirth remain a mystery.

The new study increases scientists’ understanding of the species.

Do you have suggestions for science stories? Weekly newspaper Should be covered? Do you have questions about sharks? Let us know at science@newsweek.com.

uncommon knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

#Baby #great #white #sharks #threatening #California #beaches

Image Source : www.newsweek.com